How Drone Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) Maintain Accuracy Over Time?

Drone’s Inertial Navigation Systems (INS) helps aircraft, drones, ground robots, and marine platforms navigate when satellite signals are weak or unavailable. By integrating accelerometer and gyroscope data from an IMU, an INS estimates position, velocity, and attitude starting from a known state. The challenge is drift – tiny sensor errors and modeling imperfections that accumulate over time and degrade accuracy.

So how does an INS stay accurate as minutes turn into hours? This unified article delivers the entire content in one continuous sequence, with your original text preserved and new sections added to close content gaps.

Short term vs long term errors

Understanding accuracy over time starts with separating short‑term behavior from long‑term stability. Short term covers seconds to a few minutes; long term spans many minutes to hours.

Short term errors noise and vibration

Short‑term accuracy is dominated by sensor noise and high‑frequency disturbances. Contributors include angle and velocity random walk, quantization, sample‑to‑sample jitter, and vibration coupling. Proper mechanical isolation and filtering reduce these effects. In flight logs this appears as small jitter in attitude and velocity estimates.

Long term errors drift and stability

Long‑term accuracy depends on how biases and scale‑factor errors evolve. Bias instability, temperature sensitivity, misalignment, and sensor aging make the solution drift when unaided. Even at rest, uncompensated biases integrate into position and attitude errors over time.

Why the distinction matters for UAVs

Pilots feel short‑term noise as twitchy attitude control; survey and navigation tasks are limited by long‑term drift. Designing the system requires treating both regimes differently.

Practical ways to keep accuracy over time

Warm up the IMU to a stable temperature based on the device datasheet

Use rigid mounting with vibration isolation and consistent screw torque

Calibrate biases and scale factors in controlled conditions and re‑check after major temperature changes

Use aiding sources when available -GNSS RTK, barometer, magnetometer, visual or wheel odometry

Apply motion constraints and zero‑velocity updates during stops to reset drift

Log raw IMU and estimator states to evaluate performance across missions

Quick test with Allan variance

Compute Allan variance on stationary IMU data to identify noise density, bias instability, and random walk terms. Use these to tune filter process noise and predict drift over mission duration.

What makes INS special

An INS uses a cluster of sensors – accelerometers to measure specific force and gyroscopes to track rotation. Starting from a known position and attitude, it integrates these measurements forward in time to estimate where it is and how it is moving. Because it does not rely on external signals, INS works underwater, indoors, through tunnels, and in space. The trade‑off is drift as small errors compound.

Why INS accuracy fades over time drift problem

Even precise sensors are imperfect. Temperature changes, noise, vibration, numerical integration, and slight misalignments introduce small errors that accumulate. Over time, the estimated position and attitude diverge from reality – the classic INS drift. The rest of this guide details proven ways to slow or reset that drift so accuracy is maintained across a mission.

Techniques to maintain accuracy in drone INS

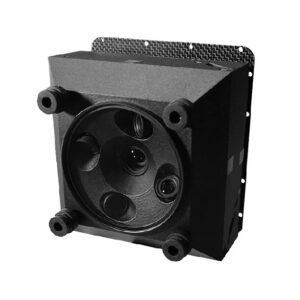

Use high‑precision IMU sensors

Aerospace‑grade IMUs exhibit lower bias and noise. Temperature compensation and stable timing further reduce initial error growth.Calibration to Correct Bias and Alignment

Calibration is like stretching before a workout – it ensures everything is aligned and ready to perform. When an INS starts up, it’s calibrated to correct for biases and alignment errors.

Sensor Bias Correction: Over time, sensors develop a small bias – a consistent error in measurement. Calibration helps account for this.

Alignment Check: Ensuring the IMU’s axes are perfectly aligned with the vehicle’s reference frame reduces systematic errors.

Regular calibration is essential, especially for systems that experience frequent environmental changes or vibrations.

Real‑Time Error Modeling and Correction

No sensor is perfect, but error modeling can predict and compensate for imperfections. By understanding how a sensor typically behaves under certain conditions, the INS can correct its calculations on the fly.

Bias Drift Modeling: By measuring how sensor bias changes over time, the system can anticipate and adjust for drift.

Random Walk Compensation: Algorithms help smooth out the random noise that can creep into sensor readings.

Error modeling is a continuous process, where the system “learns” and corrects itself in real time.

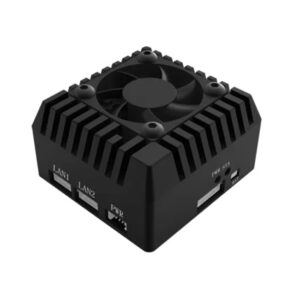

Apply advanced estimators

Use filters such as extended or unscented Kalman filters with consistent process and measurement noise. Employ zero‑velocity or zero‑angular‑rate updates when conditions allow.Fuse with external information

Blend IMU with GNSS, vision, lidar, radar, barometer, and magnetometer to provide absolute references and constrain drift.Leverage external aids and maps

Use geomagnetic maps, known landmarks, or preloaded environment models to recalibrate in GNSS‑denied areas.Build redundancy and health monitoring

Multi‑IMU setups, cross‑checks, and integrity monitoring detect faults early and improve reliability.Track emerging technologies

Quantum sensors and learning‑based estimators promise better long‑term stability as they mature.

GNSS and other aiding to maintain accuracy

When an INS runs for minutes or hours, aiding sources keep drift in check. The right mix depends on platform, environment, and required accuracy.

Coupling strategies INS with GNSS

Loosely coupled -INS and GNSS run as separate estimators while the INS consumes GNSS position and velocity updates. Simple and robust but less effective with few satellites.

Tightly coupled – A single filter fuses raw GNSS measurements with IMU states. Works with fewer satellites and provides smoother navigation through partial outages.

Deeply integrated -IMU data feeds the GNSS tracking loops. Delivers the best continuity in harsh environments at higher complexity.

GNSS options for higher accuracy

Multi‑constellation and multi‑band receivers for better geometry and faster convergence

SBAS or differential corrections for sub‑meter performance

RTK for centimeter‑level accuracy when a base or network is available

PPK when offline processing is acceptable for survey‑grade results

Antenna best practice – clear sky view, rigid mount, ground plane, correct lever arm

Non GNSS aiding methods

Magnetometer for long‑term heading stability where interference is controlled

Barometer for smooth altitude aiding and climb‑rate consistency

Visual odometry or SLAM with cameras in GNSS‑denied spaces

Wheel odometry or kinematic constraints on ground robots

Lidar odometry or depth sensors in feature‑rich environments

Ranging or beacon systems such as UWB indoors or in urban canyons

Outage handling and motion constraints

Zero‑velocity updates during planned stops to reset accumulated errors

Zero‑angular‑rate updates on stable mounts to reduce gyro bias effects

Vehicle‑specific constraints for aircraft, multirotors, and wheeled platforms

Forward‑backward smoothing in post‑processing to improve long runs

Best practices for UAV missions

Time‑sync IMU and GNSS and calibrate the lever arm between antenna and IMU

Keep the antenna away from EMI sources and spinning propellers

Log raw IMU, GNSS observations, and estimator states for diagnostics

Validate performance on repeatable routes across temperatures and payloads

Calibration and testing methods

A structured calibration and test routine prevents long‑term drift and makes accuracy predictable. Focus on thermal characterization, bias and scale‑factor calibration, alignment, and verification with repeatable tests.

Allan variance quick start

Allan variance separates short‑term noise from long‑term instabilities. Record stationary IMU data at the nominal sample rate for at least one to three hours - longer for lower‑noise sensors. Compute Allan deviation versus averaging time.

A slope near −1⁄2 indicates white noise and sets noise density

A flat region indicates bias instability and shows the best stability time

A slope near +1⁄2 points to rate random walk

Use these terms to tune filter process noise and predict drift over mission duration.

Thermal characterization

Warm the device from cold to hot and back while logging continuously. Build temperature‑bias models for gyros and accelerometers, then enable temperature compensation in firmware. Allow a short warm‑up until temperature stabilizes before missions.

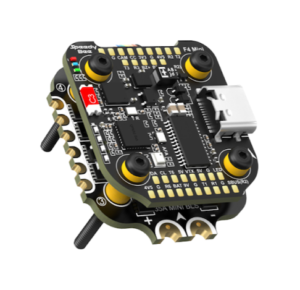

Bias and scale‑factor calibration

Perform multi‑position static calibration for accelerometers and zero‑rate calibration for gyros. Use precise rotations or a turntable to estimate scale factors and misalignment. Repeat after major mechanical changes or when the temperature range expands.

Alignment and lever arm

Mount the IMU rigidly and measure boresight angles between IMU, vehicle frame, and antenna or camera frames. Measure the lever arm between IMU and GNSS antenna and enter it in the estimator to avoid long‑term position and attitude drift.

Magnetometer and interference control

If using a magnetometer, run hard‑iron and soft‑iron calibration in a low‑interference area. Keep high‑current wires, motors, and steel parts away from the sensor and validate heading stability in hover and forward flight.

Verification checklist

Repeat a standard test route with static segments and gentle turns

Insert planned stops for zero‑velocity updates and compare drift before and after

Compare against a trusted reference when available - RTK, motion capture, or surveyed points

Review logs for estimator consistency, innovations, and temperature spread

Document calibration dates, temperatures, and results for traceability

Practical guidelines for UAVs and robots

This checklist turns accuracy theory into day‑to‑day practices for field teams.

Pre flight checks and warm up

Power on early so the IMU reaches a stable temperature before arming

Verify time sync between IMU, GNSS, and flight controller

Confirm GNSS status, correction source if used, and antenna visibility

Load the correct calibration profile for the expected temperature range

Mounting and isolation

Use a rigid mount with vibration isolation appropriate to the vehicle

Keep the IMU away from motors, power wiring, and magnetic materials

Tighten fasteners consistently and document orientation to avoid misalignment

Measure and enter lever arms between IMU, GNSS antenna, and payload sensors

Estimator setup and maintenance

Set consistent sampling rates and avoid clock drift

Tune process noise using Allan‑variance results and field logs

Enable aiding sources that match the mission - GNSS, magnetometer, barometer, visual or wheel odometry

Configure motion constraints and zero‑velocity updates where applicable

Mission planning under GNSS limitations

Plan routes with clear sky where possible and avoid reflective structures

Use takeoff hovers or pauses to let filters converge

For indoor or urban canyons, prefer visual or lidar odometry and beacon aids

Define acceptable drift windows and fallback procedures for GNSS outages

Ground robots and wheeled platforms

Calibrate wheel‑odometry scale and slip detection

Apply zero‑velocity updates during stops and at docking stations

Use heading aids - magnetometer or visual yaw - when turns are slow or stationary

Post flight analysis and logging

Log raw IMU, GNSS observations, estimator states, and temperature

Review residuals and innovations to spot bias changes or poor aiding

Compare repeated routes to track long‑term stability and calibration drift

Archive firmware versions, calibration dates, and mounting changes

Common pitfalls and quick fixes

Twitchy attitude usually indicates vibration or aggressive filtering -reduce vibration and review filter bandwidth

Growing position error at rest points to uncompensated biases - recalibrate and verify warm up

Inconsistent heading suggests magnetic interference - relocate the sensor or rely on non‑magnetic aids

Overview table - INS accuracy maintenance

| Method | Description | How it helps | Examples |

|---|---|---|---|

| Precision sensors | High‑quality IMUs with low noise and bias | Reduces initial drift and error accumulation | Aerospace‑grade IMUs |

| Calibration | Bias, scale‑factor, and alignment correction | Ensures accuracy from the start and after changes | Multi‑position accel, zero‑rate gyro |

| Error modeling | Predict and compensate sensor imperfections | Compensates bias drift and random walk | Bias‑drift models, noise adaptation |

| Advanced algorithms | Estimators with consistency checks and updates | Minimizes real‑time errors and smooths drift | EKF or UKF, ZUPT or ZARU |

| Sensor fusion | Combine INS with external references | Provides absolute updates and redundancy | GNSS, vision, lidar, radar |

| External aids | Maps and fields for recalibration where GNSS is weak | Offers positional updates in denied areas | Geomagnetic maps, UWB |

| Redundancy | Additional sensors and integrity monitoring | Cross‑checks data and detects faults | Multi‑IMU setups |

| Emerging tech | Next‑generation sensors and learning methods | Improves long‑term stability over time | Quantum gyros, ML estimators |

FAQ - maintaining INS accuracy over time

What is the difference between accuracy and stability in an INS

Accuracy describes how close the estimate is to truth at a given moment; stability describes how that accuracy behaves as time passes, especially during long periods without external updates.

Why does an INS drift even when the platform is stationary

Uncompensated biases in gyros and accelerometers integrate into attitude and position over time. Temperature changes and sensor aging also contribute.

How does GNSS aiding help maintain long‑term accuracy

GNSS provides absolute position and velocity updates that correct INS drift. Tighter integration works better in weak‑signal situations.

What warm up time is advisable before using an INS on a drone

Allow the IMU temperature to stabilize according to the datasheet and your thermal tests. This reduces bias shifts after takeoff.

How does mounting and vibration isolation impact accuracy

Poor mounting couples vibration into the IMU and increases noise. Rigid, well‑isolated mounting reduces short‑term jitter and prevents misalignment.

What is Allan variance and why is it useful

It separates noise processes across time scales, letting you estimate noise density, bias instability, and random‑walk terms to tune filters and predict drift.

How can I reduce drift during GNSS outages on UAV missions

Use motion constraints, zero‑velocity or zero‑angular‑rate updates, visual or lidar odometry, and plan pauses to let estimators re‑converge.

What data should I log to diagnose accuracy issues over time

Log raw IMU, GNSS observations, estimator states, innovations, and temperature. Review repeat missions to detect calibration drift.

Final thoughts

Maintaining INS accuracy over time is about smart sensor selection, disciplined calibration, robust estimation, and the right aiding strategy for your mission and environment. Combine these practices and you will see predictable, stable performance from takeoff to landing - even when GNSS is not always there to help.