IMU vs INS for drones – Choosing the right solution

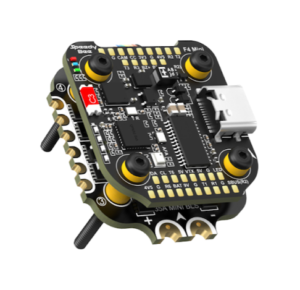

Flight controllers depend on continuous motion sensing to maintain attitude stability and to track commanded waypoints. The IMU serves as the primary sensing element, delivering raw angular-rate and linear-acceleration data. The INS builds on this by fusing those inertial measurements with GNSS or other absolute references to generate a full navigation solution. This article outlines the strengths of each system and provides a clear framework for selecting the right configuration.

IMU basics and limits

An IMU provides raw angular-rate and specific-force measurements at high frequency, making it fast, compact, and cost-efficient. Its limitation is drift: even very small bias and scale-factor errors integrate into growing attitude and position errors over time. Flight controllers therefore rely on external references—typically GNSS, magnetometers, or visual/altitude sensors—to continuously correct the IMU’s estimates. For short missions or applications where absolute position accuracy is not critical, a standalone IMU may be sufficient.

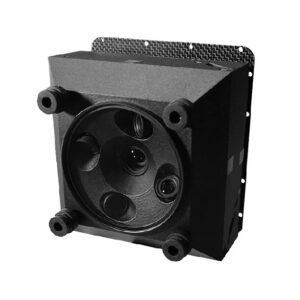

INS fundamentals and benefits

An INS fuses IMU measurements with GNSS data—and often magnetometer and barometric inputs—to produce attitude, heading, velocity, and position estimates that remain stable over long durations. The fusion filter relies on the IMU for high-rate dynamic response, while GNSS observations provide the absolute reference needed to bound long-term drift. When equipped with dual-antenna GNSS, the system can generate a highly reliable yaw solution even during low-dynamic flight conditions where magnetometers are vulnerable to local magnetic disturbances.

Mission profiles that call for an INS

Mapping missions depend on consistent camera angles and accurate geotagging to maintain uniform image geometry. Corridor inspections often encounter reflections, occlusions, and electromagnetic clutter that can degrade or momentarily distort GNSS measurements. BVLOS operations demand navigation systems that remain reliable even when external signals are imperfect. In all of these scenarios, an INS is not optional—it provides the stability layer that prevents minor disturbances from escalating into mission-level failures.

Decision checklist for buyers

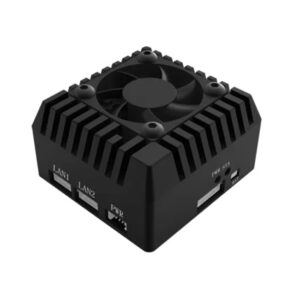

Define your required roll, pitch, and heading accuracy in degrees, along with your allowable position error in meters. Verify interface and timing compatibility—UART, CAN, Ethernet, and PPS—so the INS can synchronize cleanly with the rest of the avionics stack. Confirm that drivers exist for your autopilot platform (Pixhawk, ArduPilot, or Cube) and that the supported message rates match your control-loop requirements. Finally, assess the unit’s dimensions, mass, and power draw to ensure it fits your endurance limits and mounting geometry.

Budget thinking that stays realistic

Higher navigation accuracy and dual-antenna GNSS heading typically increase cost, as do ruggedized enclosures, temperature-stable components, and high-bandwidth interfaces such as Ethernet. Evaluate the full system rather than the sensor alone—antennas, mounting hardware, cabling, and the integration effort required to make everything work reliably. A well-chosen unit may cost more upfront, but it reduces troubleshooting time and prevents expensive delays once you’re in the field.

Common upgrade paths

Teams often start with IMU-based stabilization and only add an INS when they encounter limits in yaw stability, georeferencing accuracy, log alignment, or BVLOS regulatory requirements. If the aircraft is designed with spare space, clean mounting points, and the right interfaces already provisioned, upgrading to an INS later becomes a straightforward drop-in rather than a full rebuild.

Where to compare and what to pair

See current models in inertial navigation systems for drones.

FAQ

Will an INS improve GPS accuracy?

An INS smooths the navigation solution between GNSS updates and bridges short outages, but the absolute position accuracy is still limited by the quality, signal environment, and correction mode of the GNSS receiver. It cannot make poor GNSS data fundamentally more accurate, only more stable.Is dual-antenna heading required?

It isn’t mandatory, but it is strongly recommended whenever precise yaw accuracy is important—especially in low-dynamic flight where magnetometers are easily disturbed and cannot maintain a stable heading on their own.Can I start with an IMU and add an INS later?

Yes, provided you plan for it. Leave physical space, power availability, and clean cable routes so the INS can be added without reworking the entire airframe.